Every so often one hears that a NASA computer calculating past motions of the planets came to a stop at about the time that Joshua commanded the sun and moon to stand still in the sky (Joshua 10:12). This story has been cited by some as "proof" of the literal truth of the Bible. As far as I know, no one has ever documented that this actually happened at NASA, but the story has been repeated frequently (McIver, 1986).

Some time earlier, Karl Fezer, editor of Creation/Evolution Newsletter, was sent a copy of E. W. Faulstich's manuscript, "Moses the Astronomer and Historian Par Excellence," which was purported to contain a computer "proof" of the reality of Joshua's "long day." Faulstich is the founder of the Chronology History Research Institute (CHRI) of Rossie, Iowa. CHRI is a publisher of books, tracts, charts, and newsletters on biblical chronology. It has close ties with the Genesis Institute, founded by well-known creationist Walter Lang, founder of the Bible Science Association.

I, along with E. M. McCollister, Philip R. McLean, and Ronald G. Tabak, was asked to evaluate the manuscript. We soon determined that it was not at all connected with the story about the NASA computer. However, since Faulstich's paper generated much interest among creationists, a thorough evaluation of his paper seems in order.

His manuscript describes a rather intricate biblical chronology which he developed to tie together astronomical events and a luni-solar calendar. Faulstich claims to show that the planets were created on Wednesday, March 22, 4001 BCE, at 6:00 PM, or thereabouts, Jerusalem time. At this instant, he says, there was a close conjunction of Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the moon, as seen from Earth, and he believes that God created the planets in this configuration on the fourth day of creation.

Starting from this point, Faulstich alleges that he has established from the Bible the precise dates on which certain events happened. He asserts that the Bible gives him not only the year, month, and date of these events on the Hebrew calendar but also the day of the week for each of twenty events. His paper ends with a computer program to calculate dates on the Hebrew calendar, as well as the corresponding days of the week. According to him, he obtains perfect agreement with these twenty events. He says that this agreement confirms the literal truth of the Bible.

I find a number of problems with his work which are described in detail below.

Biblical Chronology

The first, obvious test to apply to Faulstich's work is to see how well his chronology agrees with what archeologists and biblical scholars have determined after many decades of exhaustive research. Since Faulstich claims that his chronology derives from a completely literal reading of the Bible, each of the dates within his chronology is absolutely fixed relative to all the others; thus, even a small discrepancy would mean that the biblical date of creation would not coincide with the planetary configuration crucial to his theories.

In constructing a biblical chronology, it is reasonable to adopt the working principle that events recorded in the Bible are not isolated but are set in a much larger context of Middle Eastern history. Insofar as biblical events are historical, they should be subject to the same scrutiny used by historians to evaluate any historical event. For example, not only should dates derived from biblical data be internally consistent but also, whenever synchronisms with reliable extrabiblical data can be established, they should agree with the external data. In case of conflict between several sources, greater weight must be accorded to those sources which are judged to be more reliable.

It is difficult to establish absolute chronologies of the Bible without referring to external events, because the Bible does not give us the years in which certain events occurred in a system that is readily related to world history. This is not true for Egyptian and Mesopotamian history. Particularly in the case of Mesopotamia, a large number of original documents from the first and second millennia BCE have been unearthed in the form of cuneiform records on baked clay tablets and monument inscriptions. Since these documents are contemporaneous with the events they describe, they must weigh heavily indeed in the historian's balance of evidence. Many of these documents can be dated absolutely on the basis of astronomical events, and scholars have established a highly reliable chronology of Mesopotamian history for the first millennium BCE (DeVries, 1962).

A number of precisely dateable records refer by name to contemporary Hebrew kings. For example, Assyrian documents from the reign of Shalmaneser III record that the King Ahab of Israel fought in 853 BCE at the Battle of Qarqar. Twelve years later, in 841 BCE, the "Black Obelisk" of Shalmaneser III pictures Jehu, king of Israel, paying tribute to the Assyrian king. A century later, both the Bible (II Kings 15:19) and Assyrian records record that Menahem of Israel paid tribute to Tiglath-pileser III, who reigned from 745 to 727 BCE. Later Babylonian records establish that Nebuchadnezzar II captured Jerusalem in 597 BCE. From this, one can establish that the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem took place in 587 or 586 BCE, which is how authorities date it today.

How do these records agree with the dates given in Faulstich's paper? The answer is, not well at all. To start with, Faulstich dates the destruction of the temple in 588 BCE, at least one and possibly two years too early. While one can argue that the temple was destroyed in 587 (this turns on a technical point as to whether the kings of Judah began their reign-years in the spring or the fall), Faulstich's date of 588 conflicts with the biblical record (Jeremiah 32:1; II Kings 25:8) that the siege of Jerusalem was in progress during the eighteenth and nineteenth years of Nebuchadnezzar's reign. Nebuchadnezzar's eighteenth regnal year is known to have begun in the spring of 587 (Parker and Dubberstein, 1956).

As we go back in time, the discrepancies become greater. For example, according to Faulstich, King Menahem died in 752 BCE, seven years before Tiglathpileser III ascended the throne. This conflicts with the records which state that Menahem paid tribute to Tiglath-pileser III. Again according to Faulstich, Ahab died in 869 BCE, sixteen years before he is recorded as having fought at Qarqar. Faulstich claims that the battle was actually fought earlier. These are several of a number of major discrepancies. The net result is that Faulstich's chronology is between fifteen and twenty-four years too early at the time the divided kingdom of Israel and Judah was established (between 931 and 922 BCE, according to modern scholarship).

Now, one could argue that these external synchronisms are inconsistent with the Bible and should be ignored. I think that is a difficult position to defend. One reason is that they are not inconsistent with the Bible. It is true that biblical chronology of the period is difficult; for example, if one simply adds up the reign-lengths of contemporaneous kings of Judah and Israel, one finds that equal intervals of time do not agree between the reckonings of the two kingdoms. One reason is that Judah and Israel counted the years in a king's reign differently. In Israel, the king was allowed to count the year of his accession as the first year of his reign; in Judah, the first year of the reign was counted from the following new year. This means that in Israel, the last year of the old king's reign was counted twice, once in each king's reign. This leads to counting too many years when the total reigns of several kings are added up. An example is given by the reigns of Ahab and Jehu. Between Ahab and Jehu there were two kin,, gs whose total number of reign-years adds up to fourteen.

But we already know that Ahab was still king in 853 and that Jehu was king twelve years later in 841. The excess of two years is attributed to the double counting of two years in the official count , of Israel. Other questions that have to be resolved for each kingdom involve whether the reign years began in the spring or the fall and what method each kingdom's chroniclers used to report dates affecting the other kingdoms. An additional complication comes from the fact that several of the kings established coregencies with their successors, so that some years are counted double that way.

Despite these difficulties, the general outlines of the chronology of the Divided Kingdom have been worked out to the satisfaction of most scholars (Bright, 1981; Thiele, 1965). Presently accepted chronologies sometimes differ by a few years, but they are internally and externally consistent and have withstood the test of time (Hallo, 1964). It is unlikely that these chronologies are in error by as many years as Faulstich's chronology would require.

To be fair to Faulstich, he is very aware of the problems his chronology faces as a result of archeological facts. Indeed, he has written a book on the subject, History, Harmony, and the Hebrew Kings (1986), in which he attempts to account for them. Arguments in his book are unconvincing. Accepting them would mean abandoning a large and compelling body of evidence. Ironically, the archeological evidence that Faulstich tries to discredit is precisely the same kind of corroborative evidence that other fundamentalists point to as evidence that the Bible is a reliable historical record.

If we were to accept the relative dating given by Faulstich between the creation and the establishment of the Divided Kingdom but were to correct the starting point to agree with modern scholarship, it would be necessary to move his creation date up by fifteen to twenty-four years. This means that Faulstich's creation date is at least fifteen years too late to have occurred at the time of the astronomical conjunction he cites.

And things get even worse when we consider the dates of the Exodus, which Faulstich places in the fifteenth century BCE. While the issue is not absolutely settled, a number of lines of reasoning lead most scholars to conclude that the Exodus took place in the thirteenth century BCE rather than the fifteenth, which one gets by naively counting backwards from the building of the temple by Solomon (De Vries, 1962; Freedman in Wright, 1961; Rowley, 1950). Among these reasons are the fact that, according to Exodus 1:11, the oppressed Jews in Egypt were forced to build the cities of Raamses and Pithom, which are known to have been built in the thirteenth century; the fact that many of the walled cities of Canaan mentioned in the Bible are known to have been destroyed in the thirteenth century (presumably by invading Hebrews); and the fact that the Bible does not mention Egyptian incursions into Palestine in the period between the Exodus and Solomon, although it is known that the Egyptians were pursuing an aggressive military foreign policy in the region in the late fourteenth and early thirteenth centuries. The overwhelming weight of the evidence, according to scholars, is that Ramses II (1301-1234 BCE) was the pharaoh of the Jewish oppression in Egypt and that the Exodus took place during his reign or soon afterwards.

This date for the Exodus conflicts with the biblical reckoning of 480 years from the Exodus to the building of the temple given by I Kings 6:1. However, the figure of 480 years also conflicts with other biblical data. For example, the number of generations listed in the Bible from Moses to Solomon is only six (Exodus 6:23; Ruth 4:20-22), which is much too few for such a long period. So it is unwise to accept the 480-year figure uncritically. It is virtually certain that this figure was obtained by later chroniclers multiplying a conventional forty years per generation by twelve generations and that the actual amount of time was much smaller (De Vries, 1962; Freedman in Wright, 1961).

If we accept this argument and Faulstich's pre-Exodus relative chronology, then the astronomical conjunction cited by Faulstich occurred approximately two centuries before the planets were created.

Calendrical Matters

But suppose we ignore these problems and accept Faulstich's chronology for the moment. What of his next claim that the biblical dates and days of the week agree perfectly with the astronomical facts? Faulstich gives an example:

If, for example, Moses read the Law on the first day of the 11th month of the 40th year on a Saturday, the lunar-solar calendar for 1422 BC can be examined to see if the text is correct. . . Some 20 dates studied have been found to be correct. Calculating the chances, we have seven days in a week, therefore the first date would suggest one in seven, the second 1/49, the third 1/243, the fourth 1/2401, etc. The probabilities of 20 being correct by chance would be some 97 billion to one.

Three questions have to be answered. First, can one really derive these dates from biblical data alone? Second, do the dates and days of the week given by Faulstich really coincide? And finally, if they do coincide, what is the most likely reason for this?

Faulstich cites a number of biblical passages in support of his first claim. I have examined them and find that, although in many cases there is information that would allow the month and day on the luni-solar calendar to be determined, there is little information that would allow one to determine the day of the week. I wrote to Faulstich about this. He gave in support of his contention that Moses received the Ten Commandments on a Saturday both Jewish tradition and Exodus 24:16 (NEB), which states: "The glory of the Lord rested upon Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered the mountain for six days; on the seventh day he called to Moses out of the cloud." Faulstich interprets "seventh day" to mean "Saturday." When I pointed out that it could just as well mean the seventh day after the previously mentioned event, he responded that the Jews used numbers to count their days. Perhaps, but I find this rather flimsy evidence. I note, for example, that Exodus 19:16, which refers to the same event as does Exodus 24:16 (Gray, 1971), says that, just before Moses climbed up the mountain to receive the law from God: "On the third day, when morning came, there were peals of thunder and flashes of lightning, dense cloud on the mountain and a loud trumpet blast; the people in the camp were all terrified." If Faulstich's interpretation were correct, then this passage would have to be interpreted as saying that Moses went up to receive the law on a Tuesday, not a Saturday.

Giving Faulstich the benefit of the doubt, we can press on and ask if the dates he gives are consistent with the ancient Hebrew calendar. I find that they are not. The Hebrew calendar in use during biblical times is different from today's version. Today's calendar is based upon a conventionalized calculation of the positions of the moon and sun which is fairly straightforward, despite some special rules (dehioth) which prevent certain holy days from occurring on certain days of the week (Spier, 1952). However, in biblical times, even as late as the first century of the Common Era, the first day of the Hebrew month began at sunset on the first day that the crescent of the new moon was visible before sunset. If the moon was not actually seen before sunset on the day of the new moon, the beginning of the month was postponed until the following day. It follows (since the average length of time between one new moon and the next is 29.53 days) that a Hebrew month in ancient times was either twenty-nine or thirty days long.

This method was in general use in many parts of the Middle East for thousands of years. One consequence of this method of determining the beginning of the month is that the day on which a given lunar month began cannot be determined with mathematical certainty since bad weather may have prevented priests from actually observing the lunar crescent on the first day that it could theoretically have been seen. Nor is weather the only consideration; poor visibility conditions in the Fertile Crescent near the horizon make the new moon easy to miss even in good weather (Neugebauer, 1951). Therefore, when the sighting was delayed, for whatever the reason, the preceding month automatically had thirty days—regardless of the astronomical facts. Many such instances are known from cuneiform records (Landon and Fotheringham, 1928).

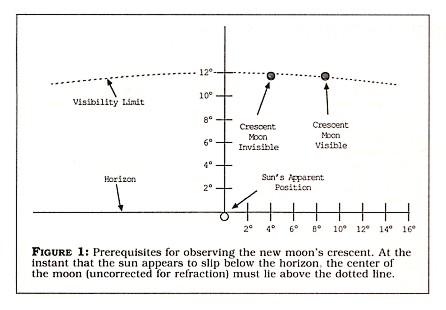

Even assuming perfect weather, it is not simple to predict the time of first visibility of the lunar crescent. The time between actual new moon and first visibility depends, among other things, upon the observer's latitude and longitude on Earth, the time of the year, the position of the moon in its orbit, and the constantly changing orientation of the moon's orbit. This has been investigated extensively because many of the cuneiform records give sufficient information for the lengths of particular months to be determined. The work of Fotheringham (1910) and Schoch (Langdon and Fotheringham, 1928) has made it possible to determine mathematically the earliest moment at which the crescent moon might be visible. Even though uncertainties due to weather and observing conditions near the horizon still cannot be resolved, these scholars have obtained excellent agreement between the cuneiform records and independent calculations. The moon must stand high enough above the horizon at the moment of sunset (as illustrated in Figure 1) or it cannot be seen with the naked eye. The moon will be visible (given good weather and atmospheric conditions near the horizon) only if its center is higher than the dotted line at the instant that the sun's upper limb disappears from view below the horizon.

Faulstich, on the other hand, has used a very simple mathematical model to determine the beginning of months in the Hebrew calendar. He has assumed that the moon moves at a constant velocity around Earth instead of at a significantly varying orbital velocity. His model also fails to take into account the fact that the moon is constantly moving farther from Earth (by about four centimeters per year), so that the month is getting longer, and, moreover, it fails to consider the significant slowing of Earth's rotation by the tides. Faulstich's computer program makes no attempt to determine the moment of first visibility of the lunar crescent as illustrated in Figure 1, nor does it take into account the substantial influence of the observer's longitude and latitude on the moment of first visibility. Finally, Faulstich's method is mathematically deterministic and therefore inherently unrealistic because it takes no account of possible problems with weather or atmospheric conditions near the horizon.

I find that many of the months in which Faulstich has dated events cannot have begun on the days he calculates. For example, his date for Moses reading the law (quoted previously) is Saturday, on the first day of the eleventh lunar month of the luni-solar year 1422-1421 BCE. I find that at sunset on the preceding Friday, the moon was still too close to the sun to have been visible anywhere in the Sinai peninsula or its environs (including Jerusalem), where the events reported are supposed to have taken place. Therefore, the first day of the eleventh lunar month of that year cannot have been a Saturday. The very earliest it could have been was a Sunday. Indeed, it could even have been a Monday if visibility conditions on Saturday were poor. Therefore, if Faulstich's identification of the day of the week is correct, the event could not have taken place in the luni-solar year 1422-1421 BCE. Since this is a key "anchor" date, Faulstich's entire chronology is put in jeopardy.

One can go even further and state that, if the dates and days of the week had agreed with Faulstich's calculation, then they must have been calculated, not observed. This is so because Faulstich's dates are inconsistent with the astronomical facts but consistent with a simple lunar ephemeris in which the moon moves at a uniform rate. Since it is not until quite late (c. 500 BCE) that the ancients were able to predict some of the astronomical events that are required for a successful luni-solar calendar (Neugebauer, 1955, 1975), it follows then that these dates would have to have been incorporated into the Bible after 500 BCE, which would contradict Faulstich's assertion that Moses himself wrote these books. Scholars have known for over one hundred years that Moses was not the author of the Pentateuch (the so-called Five Books of Moses); these documents were the product of many hands and were written down between the tenth and fifth centuries BCE, although they recount traditions that are much older. Strict fundamentalists are virtually alone today in accepting the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch (Hyatt, 1971).

Joshua's Long Day

Faulstich claims that he has evidence that the "long day" in the Bible, when Joshua commanded the sun to stand still, really took place. His argument goes as follows: according to astronomical calculations, the conjunction in 4001 BCE took place on Thursday morning at about 6:00 AM Greenwich. According to Faulstich's ideas, the conjunction should have happened when God finished creating the planets on the evening of day four (Wednesday). Therefore, the creation of the planets occurs a half-day too early. He proposes that the half-day discrepancy is due to there having been an extra-long day in Joshua's time.

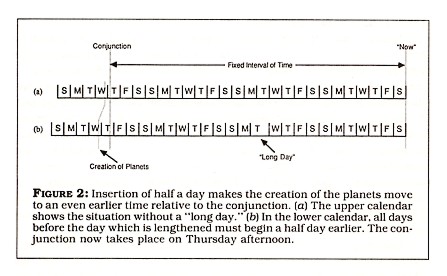

Unfortunately, there is at least one fly in this ointment. If there had been an extra-long day in Joshua's time, the effect would have been to move the creation of the planets to an even earlier time, relative to the alleged significant conjunction. This is easy to see. Assume, as does Faulstich, that the motion of the moon and planets gives us a very good clock. This means that the interval of time between two events involving the motion of these bodies (measured in what astronomers call "Ephemeris Time") is fixed and unchanging. For example, the interval of time between Faulstich's conjunction and "now" (the present instant) is fixed.

If we make one of the days between the conjunction and "now" longer by half a day, the interval of time between the creation of the planets and "now" becomes longer by half a day. Since recent dates are unaffected, it follows that the additional time must be accounted for by moving the creation of the planets to an earlier instant. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

The effect is the exact opposite of what happens when we remove time from the chronology. Earlier we found that if we removed fifteen years from the chronology of the Divided Kingdom, the date of creation would be moved to an instant fifteen years later than the astronomical conjunction. Likewise, if we add half a day in the form of "Joshua's long day," the date of creation would be moved yet another half a day earlier, relative to the conjunction. Since Faulstich's creation day is already too early, this makes matters worse for his theory, not better. To move the moment of planetary creation to a later time, he would have to remove. a half day by making Joshua's day shorter. This, of course, would be biblically unacceptable, even though the hypothetical changes are very small scale.

It should also be noted that the same thing would happen to all of Faulstich's lunar dates prior to Joshua. With an additional half-day inserted, the new moons would occur later on the day count, not earlier, and would postpone the beginning of still other months to later days in the week. This, in turn, would exacerbate Faulstich's problem of making his chronology agree with the days of the week.

When I pointed out this difficulty to Faulstich, he responded that perhaps only the sun and moon stopped and that perhaps the motion of the planets was not affected. This idea doesn't work either. The planets move very slowly against the background of the stars, so the time of the conjunction is determined almost entirely by the motion of the moon and is hardly affected at all by the motion of the planets. With this modification, the conjunction remains stubbornly fixed on Thursday morning.

Faulstich provides a simple computer program for calculating the Hebrew date that makes a correction for the half (actually, 0.4) day. Unfortunately, the correction is applied with the wrong sign. Indeed, the program would not even run as printed! Faulstich later provided me with some programs written in Applesoft BASIC which did run correctly, apparently programmed by an associate of his. One was a program for calculating dates on several calendars, while others calculate lunar and planetary positions with reasonable accuracy. Biblical exegesis was not materially affected.

How Rare Are Conjunctions?

The width of a conjunction or alignment is the difference between the largest and the smallest geocentric longitude of the four bodies involved. In his paper, Faulstich states that the odds against a one-degree (half-width) alignment of the moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars are 16,796,160,000 to one. He doesn't actually say that this is per year, but from the context it is clear that this is what he means. The alleged rarity of this phenomenon is a major part of Faulstich's argument that the planets must have been created at that time.

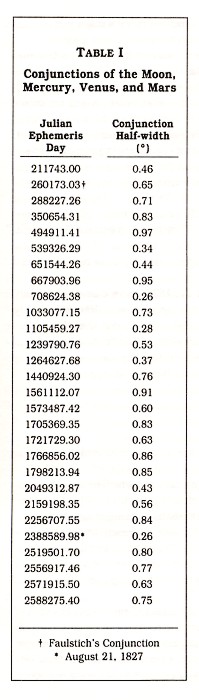

I calculated that the actual odds in any year were of the order of a few hundred to one. When I pointed this out to Faulstich, he expressed doubt that I was correct and challenged me to find other similar alignments. As it happened, I had already done so. The dates and half-widths of the alignments I found are shown in Table I. (These alignments given in the table after 1410 BCE have been checked independently by E. M. Standish of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using the JPL Ephemeris DE 102, which is the current standard ephemeris. Agreement between my calculations and his is excellent.) The times of the events are given as the Julian Ephemeris Date (not the Julian Date) of the configuration. My search covered the seven-thousand-year period from 4500 BCE to 2500 BCE. I found twenty-eight such alignments, or an average of one per 250 years. Of these, thirteen, or one per 538 years, are closer than the one cited by Faulstich. It is evident that quadruple conjunctions like the one in 4001 BCE are not rare at all. Faulstich has overestimated the odds against such a configuration by a factor of at least 3 x 107.

For example, the conjunction of August 21, 1827, had a half-width of only 0.26 degrees, just four-tenths that of Faulstich's conjunction of 4001 BCE. Surely if Faulstich's ideas were correct we would expect to find that something spectacular happened on that date, something much more wonderful than the creation of the planets! As far as I can determine, however, that day was just an ordinary day in history, indistinguishable from any other hot day in August.

Conclusions

I have demonstrated that Faulstich's conclusions conflict with both biblical and extrabiblical historial evidence and with astronomical and calendrical facts. Contrary to Faulstich's claims, the planetary alignment upon which he bases his conclusions is in no way unusual. Although the motto of Faulstich's CHRI is "Stressing Truth Through Scientific Methods," it is hard to see how the arguments he presents in his paper can be called "scientific." Scientifically, conjunctions are of interest only if they provide special observing conditions, like eclipses, and to accord them greater significance smacks of astrology and numerology, not science. Surely one must come up with more than this to refute the overwhelming scientific evidence that exists for the great age of Earth.

However, Faulstich deserves credit for one aspect of this work. His idea of using a modern computer program to determine ancient dates on the Hebrew luni-solar calendar has merit, even if it is not as straightforward to apply as he thought and even if its execution was flawed. However, I personally believe it unlikely that many dates can really be pinned down with this technique, since the notion that the Bible is a historical record that provides the required information with sufficient reliability for this to be done is suspect. As Neugebauer has shown, even the interpretation of ancient documents such as original cuneiform astronomical tablets requires great care, and a similar analysis of a document such as the Bible would be perilous indeed.

Acknowledgements

I thank Eugene W. Faulstich for his assistance in answering my questions about his work. Despite the fact that I did not hide my skepticism about his theories, he has been a willing and courteous correspondent and has provided more than I asked for. I also thank Frank Arduini, John Cole, Karl Fezer, E. M. McCollister, Philip R. McLean, and Ronald G. Tabak who provided valuable commentary.

Special thanks are due to Prescott Williams, professor of Old Testament languages and archeology at the Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, who gave me valuable insight into Old Testament chronology and suggested some important sources of which I was unaware.

Finally, I thank Robert J. Schadewald. His very careful reading of this manuscript and his correspondence with me about Faulstich's work has been invaluable.

References

Bright, John. 1981. A History of Israel. Third edition. Westminster Press.

De Vries, S. J. 1962. In The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Volume 1. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, pp. 580-599.

Faulstich, E. W. (n.d.) "Moses the Astronomer and Historian Par Excellence." Privately printed.

——. 1986. History, Harmony, and the Hebrew Kings. Spencer, IA: Chronology Books.

Freedman, David Noel. 1961. "The Chronology of Israel." In G. E. Wright (editor), The Bible and the Ancient Near East. Doubleday, p. 207.

Fotheringham, J. K. 1910. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomy Society. 52:527-531.

Gray, John. 1971. The Interpreter's One-Volume Commentary on the Bible. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Hallo, W. W. 1964. "From Qarqar to Carchemish: Assyria and Israel in the Light of New Discoveries." In The Biblical Archaeologist Reader, Volume II. Anchor Books, pp. 152-188.

Hyatt, J. Philip. 1971. "The Compiling of Israel's History." In The Interpreter's One-Volume Commentary on the Bible. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, pp. 1082-1089.

Langdon, S., and Fotheringham, J. K. 1928. The Venus Tablets of Ammizaduga. London.

McIver, Tom. 1986. "Ancient Tales and Space-age Myths of Creationist Evangelism." The Skeptical Inquirer. Volume 10, pp. 258-260.

Neugebauer, Otto. 1951. In Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 95: 110-116.

——. 1955. Astronomical Cuneiform Texts. Springer-Verlag.

——. 1975. A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Part 1. Springer-Verlag.

Parker, R. A., and Dubberstein, W. H. 1956. Babylonian Chronology 626 BC-AD 75. Brown University Press.

Rowley, H. H. 1950. From Joseph to Joshua. Oxford University Press.

Spier, Arthur. 1952. The Contemporary Hebrew Calendar. Behrman House.

Staples. W. E. 1962. In The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Volume 1. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Thiele, E. R. 1965. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Revised edition. Eerdmans.

William H. Jefferys is the Harlan J. Smith Centennial Professor of Astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin. He specializes in the fields of astrometry and dynamical astronomy, and serves as the astrometry team leader for the NASA Hubble Space Telescope project.© 1987 by William H. Jefferys